Tutorial

Alda 101

Before we get started, go ahead and install Alda, if you haven’t already!

We will use the Alda REPL (Read-Evaluate-Play Loop) at first, to experiment a little with Alda syntax. To start the REPL, type:

alda repl

You can type snippets of Alda code into the REPL, press Enter, and hear the results instantly.

Notes

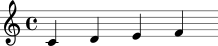

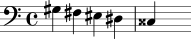

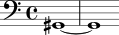

Let’s start with a simple example. Let’s translate this measure of sheet music into Alda code:

Here we have four quarter notes: C, D, E and F. The Alda version of this is:

c d e f

Try typing this into the REPL and pressing Enter… nothing happens. Why? Well, we haven’t told Alda what instrument we want to play these notes. Let’s go with a piano:

piano: c d e f

Now you should hear a piano playing those four notes.

It’s important to note that the piano is now the currently active instrument. Until you change instruments, any notes that you enter into the REPL will continue to be played by the piano.

Octaves

Let’s add some more notes.

g a b > c

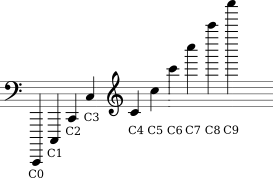

You should hear the piano continuing upwards in the C major scale. An

interesting thing to note here is the >. This is Alda syntax for “go up to the

next octave.” An octave, in scientific pitch

notation, starts on a C and goes up to a B. Once you

go above that B, the notes start over from C and you are in a new octave. In

Alda, each instrument starts in octave 4, and remains in that octave until you

tell it to change octaves. You can do that in one of two ways: you can use <

and > to go down or up by one octave; or, you can jump to a specific octave

using o followed by a number. For example:

o0 c > c > c > c > c > c > c > c > c > c

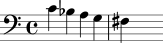

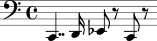

Accidentals

Sharps and flats can be added to a note by appending + or -.

o4 c < b- a g f+

You can even have double flats/sharps:

g+ f+ e+ d+ c++

As a matter of fact, a note in Alda can have any combination of flats/sharps. It usually isn’t useful to use more than 2 sharps or flats (tops), but there’s nothing stopping you from doing things like this:

o4 c++++-+-+-+

The above is a really obtuse and unnecessary way to represent an E (a.k.a. a C-sharp-sharp-sharp-sharp-flat-sharp-flat-sharp-flat-sharp) in Alda.

Note lengths

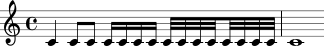

By default, notes in Alda are quarter notes. You can set the length of a note by adding a number after it. The number represents the note type, e.g. 4 for a quarter note, 8 for an eighth, 16 for a sixteenth, etc. When you specify a note length, this becomes the “new default” for all subsequent notes.

o4 c4 c8 c c16 c c c c32 c c c c c c c | c1

You may have noticed the pipe | character before the last note in the example above. This represents a bar line separating two measures of music. Bar lines are optional in Alda; they are ignored by the compiler, and serve no purpose apart from making your score more readable.

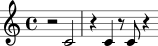

Rests

Rests in Alda work just like notes; they’re kind of like notes that you can’t hear. A rest is represented as the letter r.

r2 c | r4 c r8 c r4

Dotted notes

You can use dotted notes, too. Simply add one or more .s onto

the end of a note length.

trombone: o2 c4.. d16 e-8 r c r

Ties

You can add note durations together using a tie, which in Alda is represented as a tilde ~.

piano: o2 g+1~1

Chords

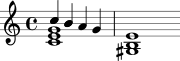

When you play multiple notes at the same time on a single instrument, that’s a chord! In Alda, a chord is multiple notes separated by slashes /.

o4 c1/e-/g/b

Notice that, just like with a sequence of consecutive notes, specifying a note length on one note of a chord will make that the default note length for all subsequent notes.

A convenient feature of Alda is that the notes in a chord do not need to be the same length. This can be useful if you’re writing a piece of music that features a melody weaving in and out of chords:

o4 c1/e/g/>c4 < b a g | < g+1/b/>e

Also note that it is possible to change octaves mid-chord using < and >. This makes it convenient to describe chords from the bottom up or top down.

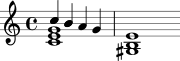

Voices

Another way to represent notes played at the same time in Alda is with voices. The same example we just wrote with chords could also be written like this using a combination of chords and voices:

V1: o5 c4 < b a g | e1 V2: o4 c1/e/g | < g+/b

To exit the Alda REPL, press Ctrl+D or enter :quit.

Writing a score

So far, we have been feeding Alda some code, line by line, and hearing the result each time. This is a good way to test the waters and see how small pieces of code sound before you commit to them. When you’re ready to set some music down in stone, it’s time to write a score.

To Alda, a score is just a text file. You can use any text editor you’d like to

create this text file. By convention, the file’s name should end in .alda.

Create a blank text file in whatever directory you’re currently in in your

terminal, and name it test.alda.

Type the following into test.alda:

bassoon:

o2 d8 e (quant 30) f+ g (quant 99) a2

Then, run alda play --file test.alda. You should hear a nimble bassoon melody.

Attributes

You may have noticed that I snuck in a new syntax here. I was going to get to

that, I promise! (quant XX) (where XX is a number from 0-99) essentially

changes the length of a note, without changing its duration. The number

argument represents the percentage of the note’s full length that is heard.

Notice, when you play back the bassoon melody above, how the F# and G notes

(quantized at 30%) are short and staccato, whereas the final A note (quantized

at 99%) is long and legato.

quant (short for quantization) is one example of an attribute that you can set within an Alda score. volume is another example; it lets you set the volume of the notes to come. Like most attributes, volume (which can be abbreviated as vol) is also expressed as a number between 0 and 100.

Try editing test.alda to look like this:

bassoon:

o2 d8 e (quant 30) (vol 50) f+ g (quant 99) a2

Run alda play --file test.alda again to hear the difference in volume between the first two and last three notes.

Multiple instruments

Finally, we come to the meat of writing a score: writing for multiple instruments.

An Alda score can contain any number of instrument parts, which are all played simultaneously when the score is performed. Try this out in your test.alda file:

trumpet:

o4 c8 d e f g a b > c4.

trombone:

o3 e8 f g a b > c d e4.

The key thing to notice here is that we have written out individual parts for two instruments, a trumpet and a trombone – one after the other – and when you play the score, you will hear both instruments playing at the same time, in harmony.

You can also write out the parts a little at a time, like this:

trumpet:

o4 c8 d e f g

trombone:

o3 e8 f g a b

trumpet:

a b > c4.

trombone:

> c d e4.

Notice that this example sounds exactly the same as the last example. This demonstrates another important thing about writing scores in Alda: when you switch to another instrument part, the instrument part you were working on still exists, in sort of a “paused” state, ready to pick it back up where you left off once you switch back to that instrument.

Global attributes

Recall that you can change things like an instrument’s volume by setting attributes. tempo is another thing you can change by setting an attribute. Let’s try it:

trumpet:

(tempo 200) o4 c8 d e f g a b > c4.

trombone:

o3 e8 f g a b > c d e4.

Wait a minute… did you hear that? The trumpet took off at 200 bpm like we told it to, but the trombone remained steady at the default tempo, 120 bpm! This is actually not a bug, but a feature. In Alda, tempo (along with every other attribute) is set on a per-instrument basis, making it entirely possible for two instruments to be playing at two totally different tempos.

Global attributes are written just like regular attributes, but with an exclamation point on the end. Try this on for size:

trumpet:

(tempo! 200) o4 c8 d e f g a b > c4.

trombone:

o3 e8 f g a b > c d e4.

tempo! sets the tempo for all instruments, at the specific time in the score where you place it. Try playing around with this bit of Alda code, moving the (tempo! 200) to different places in the score. Try out some different tempos other than 200 bpm.

Markers

We’ve already gone over a lot, but I’d like to show you how to do just one more thing in Alda – it’s an important one because it helps you keep your instruments synchronized in perfect time.

The concept behind markers is assigning a name to a moment in time. A name can contain letters, numbers, apostrophes, dashes, pluses, and parentheses, and the first two characters must be letters. The following are all examples of valid marker names:

chorusvoiceInlast-noteverse(2)bass+drums

Using markers is a two-step process. Place a marker by sticking a % before

the name, and then jump to it by sticking a @ before the name. To

demonstrate, let’s go back to our trumpet and trombone example. Let’s have a

tuba come in right on the last note. We can do that by placing a marker in

either the trumpet or trombone part, right before the last note, and then jump

to that marker in the tuba part that we’ll create:

trumpet:

o4 c8 d e f g a b > %last-note c4.~2

trombone:

o3 e8 f g a b > c d e4.~2

tuba:

@last-note o2 c4.~2

So, that’s Alda in a nutshell.

If you’d like to go deeper, check out the docs or come chat with us on Slack!